Hospitals Need To Review Their Outpatient Services For More Revenue

Posted by Mitch Mitchell on Jul 7, 2015

It turns out that I don't write enough about health care finance on this blog, even though that's where I make most of my money. I figured that since I just had an article show up in a magazine called MiraMed Focus, then online titled 5 Tips Towards Finding Missing Revenue, that it was time for an article here on the overall subject as it pertains to outpatient revenue.

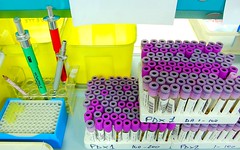

via Compfight |

Why outpatient revenue? Well, before I go there I want to make sure everyone knows the difference between inpatient and outpatient, in case someone who's not in health care decides to read this, which wouldn't hurt to know what goes on.

In a nutshell, inpatient revenue means any revenue generated when someone has to stay in the hospital for more than one night. Under certain circumstances a one night stay could be considered an inpatient stay but generally not (unless hospitals don't have any control over their physicians, but I don't want to go there right now).

Outpatient revenue is everything else. It could be a lab test or a radiology scan. It could be getting a blood transfusion or cancer infusion drugs. It could be an emergency room visit or a one day surgery. Anything that's not inpatient is outpatient.

What has happened for at least 50 years that still happens these days? Most hospital CFOs (that's chief financial officer) or VP's of finance (same position most of the time, just a different title) will give a lot of their time towards working on budgets based on inpatient revenue.

Not that it's a bad place to start, because it's the one area where, for the most part, everything is standard and thus easy to calculate. Using insurance more than diagnosis (why a person is in the hospital), although diagnosis ends up being a part of it, CFOs can figure out how much revenue was generated on inpatients quickly since there are way fewer patients who are inpatients than outpatients, estimate how much money is generated from there, then take a blanket figure from outpatient services and come up with how much needs to be generated to bring in the amount of cash needed to pay everyone. The idea is that if revenue hits certain numbers, contracts on the back end will give hospitals the money they need to survive. That's not a bad plan.

|

Except... what I've found over the course of more than 20 years is that it's not that easy at all. Rather, it's easy but so inaccurate that hospitals are hurting themselves more often than not because old school thinking seems to have lead to forgetting that since the early 90's inpatient stays have drastically decreased because more things can be done as outpatients these days. Not paying attention to that will shut a hospital down with no one knowing why; that's scary stuff, and it's something I fight against.

Think about it. Back in the 80's if someone had a knee operation that was a 4-day stay. Anything that had to do with the heart was at least 7 days. These days, not only are those surgeries usually done as outpatients but things like back surgery, where someone might have a disk replaced, and many other maladies are outpatient services also. A patient might end up staying overnight for observation but that's still an outpatient service.

Take that into consideration first. Then look at the next thing under consideration, that being the overwhelming volume of outpatient services that can overwhelm revenue.

Let's use lab as an example. I'm betting most people don't know that it's possible that a hospital could actually bill for more than 200 lab services in one sitting for one patient; yep, could happen. Let's say a parent takes a child in for lab tests because the child is exhibiting allergic symptoms to something. Initially a doctor might want to test for 20 or 25 different things, which might be childhood related. If all of those came up negative the search has to spread further.

Here's the thing. Some of those lab tests might use the same code for those tests (called a CPT-4 code or procedure code). No matter; if testing for something different, hospitals are supposed to charge that code multiple times. The medical records will show all the tests that were run for support, so it's all good.

However, what I often see is that many hospitals don't know this fact. So they'll only charge 1 item for multiple tests because there's only the one code. Thus, a hospital could be cheating itself out of multiple payments for one code and would be showing a loss they know nothing about because no one thought to verify whether they could bill multiple times for a single code.

via Compfight |

Overall, a lab test doesn't pay all that much if it's separately reimbursable but think this way; based on multiples, wouldn't you think that would end up being a lot of money? Sure, on an inpatient claim you might generate upwards of $100,000 or more in revenue (which no one pays, not even self pay patients in today's world) while you probably have at least 200 outpatients for every inpatient getting lab services, having multiple tests run, and most probably having other outpatient services provided while they're there; that's fairly common as well.

I used lab as an example because it's easy to explain. However, there are lots of other services where multiples can be charged for but aren't for a variety of reasons, the main one being no one knowing that they can. In the article the link goes to above, I mentioned how a hospital had shut down an entire department that would have generated lots of revenue and money because they weren't charging properly and no one knew it. If only I'd been there beforehand... sigh...

Overall, this is what I do... at least what I'm known for. I help hospitals generate a lot of revenue they didn't know about, which in turn brings in a lot more money. I don't do it by looking at inpatient services; there's nothing for me to do there. I look at outpatient services because that's where hospitals can find the biggest boost in revenue that will benefit them in the long run.

I start by reviewing a hospital's charge master, look at revenue, and then meet with departments to find out what they know and what they need to know. Then it's planning, training, verification and... hopefully... better results.

When I can get a CFO to actually talk to me that's what I tell them. Those who give me a shot have seen great results (well, maybe not CAH, or critical access hospitals, but that's the fault of contracting and not anything I do) and affected great turnarounds. Those that haven't, or don't keep up with it... that's not my fault either.

I know people in the community think their hospital bills are too high as it is. Trust me, in many ways it's not high enough, and it's not something that's coming out of your pocket if you have insurance. Yet it's something that could keep your local hospital from closure; who wants that?